May 1, 03

Like Redwoods Under

the Sea

by Taylor Sisk

Twenty miles, give or take off the coast of Florida, stretching

from Daytona Beach down to Ft. Pierce, hugging tight to the continental

shelf, deep-water coral reefs called Oculina varicosa grow on the

ocean floor, 200 to 300 feet beneath the water’s surface.

The deep-water Oculina reefs are quite unique, perhaps the only

of their variety in the world. As such, in 1984, the National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries

Service designated a 92-square-mile portion of these reefs as a

Marine Protected Area (MPA), meaning that no fish trawling is allowed

within its boundaries. In 1994, the MPA was closed to all manner

of bottom fishing; in 2000, the area was expanded to 300 square

miles.

Twenty miles, give or take off the coast of Florida, stretching

from Daytona Beach down to Ft. Pierce, hugging tight to the continental

shelf, deep-water coral reefs called Oculina varicosa grow on the

ocean floor, 200 to 300 feet beneath the water’s surface.

The deep-water Oculina reefs are quite unique, perhaps the only

of their variety in the world. As such, in 1984, the National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries

Service designated a 92-square-mile portion of these reefs as a

Marine Protected Area (MPA), meaning that no fish trawling is allowed

within its boundaries. In 1994, the MPA was closed to all manner

of bottom fishing; in 2000, the area was expanded to 300 square

miles.

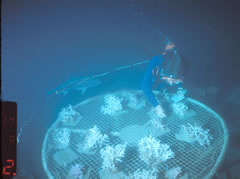

(above: healthy Oculina)

Walk into a bait shop anywhere along the coast of Florida, though,

and odds are the fishing map you pull from the rack will have no

indication of the above. No mention of fishing restrictions, no

acknowledgement of an MPA. And that’s a problem.

It certainly doesn’t make John Reed’s job any easier.

Reed is a marine scientist with the Harbor Branch Oceanographic

Institution in Ft. Pierce. He’s presently co-principal investigator

on an eight-day expedition led by the NOAA Undersea Research Program

to learn more about the Oculina reefs. Reed has been studying the

Oculina for 25 years; it’s been the primary focus of his entire

career. It was he, in fact, who nominated the Oculina as a protected

area.

“When I was first out of graduate school,” says Reed,

“I was hired at Harbor Branch, and this was  just

after they’d discovered the deep-water Oculina reefs using

the Johnson-Sea-Link submersible. They had just come across one

of these 60 to 100 foot high reefs covered with coral. “My

first study, in 1976, was to see what lived in the coral, what used

it for habitat. And over the next 10 years I did a number of studies.

I began to study the invertebrates, and what I found out was that

a small coral with a head the size of a basketball could hold up

to over 2,000 individual animals and hundreds of species, from worms

to crabs to shrimp to fish – it was an incredibly bio-diverse

environment that we had never known about before.

just

after they’d discovered the deep-water Oculina reefs using

the Johnson-Sea-Link submersible. They had just come across one

of these 60 to 100 foot high reefs covered with coral. “My

first study, in 1976, was to see what lived in the coral, what used

it for habitat. And over the next 10 years I did a number of studies.

I began to study the invertebrates, and what I found out was that

a small coral with a head the size of a basketball could hold up

to over 2,000 individual animals and hundreds of species, from worms

to crabs to shrimp to fish – it was an incredibly bio-diverse

environment that we had never known about before.

(at right: a bivalve imbedded in

Oculina)

“By 1980, we realized that this was a totally unique habitat

found nowhere else in the continental United States. And possibly

nowhere else in the world. “At the same time, I began to look

at how fast  the

coral grows. So my next study was to see how old their heads were.

We were seeing coral heads the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. I did

a study over two years and found that they actually grow very slowly,

about a half an inch a year. So a large head could easily be 100,

200 years old. Then I did a core – which is just a sample

within one of these reefs – to get some of the reef structure,

and we did radio- carbon dating of the dead coral that came from

the inside of the reef.”

the

coral grows. So my next study was to see how old their heads were.

We were seeing coral heads the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. I did

a study over two years and found that they actually grow very slowly,

about a half an inch a year. So a large head could easily be 100,

200 years old. Then I did a core – which is just a sample

within one of these reefs – to get some of the reef structure,

and we did radio- carbon dating of the dead coral that came from

the inside of the reef.”

(at left: a coral growth table)

What Reed and his colleagues learned was that the particular coral

they had examined was 8,000 years old, meaning that the entire reef

structure had been around 10,000 to 12,000 years. “We also

came to realize,” Reed continues, “how fragile the coral

was: the branches themselves are the diameter of a pencil, and the

reefs form into big bushes. So imagine how any heavy weight, like

fishing gear, dragging through it, could very easily crush it.

“At that time, in the early ‘80s, there was indication

that boats were coming down from the Georgia coast and fishing with

roller trawls; they could fish on the bottom of high-relief areas

– they had wheels on chains so that they could easily roll

over the bottom of the ocean.”

These rare coral reefs, home to hundreds of species, including commercially

important fish, were being destroyed. It would take hundreds of

years to restore them, if they could be restored at all. Thus the

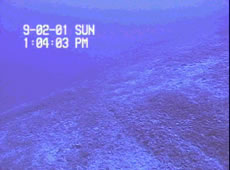

need for protection. (at right: trawl

tracks through a destroyed Oculina reef)

“My main concern is that while on paper this has been a protected

area since 1984, it’s still being heavily fished,” both

by poachers and the unaware. “Tremendous damage can be done

by an errant shrimp trawler going across one of these pristine reefs.

One pass can destroy a great many reefs.”

Protected areas mean little if not for, first and foremost, public

awareness. Maps indicating the boundaries of the MPA would certainly

help. As will a further understanding of the importance of these

national natural treasures.

“There is public outcry about making too many protected areas,”

says Reed. “But the size of the MPA is really a miniscule

percentage of the overall area. “They’re like the redwood

forests. These reefs are thousands of years old. And there are no

others like them in the world.”

This report was prepared by Taylor Sisk, a journalist,

marketing communications consultant and film & video producer.

He has written for The Independent, San Francisco Weekly, Southern

Exposure and the Oxford Dictionary of the Social Sciences; was a

writer/researcher on the History Channel: The Ellis Island Experience

(CD-ROM; South Peak Interactive); and was director/producer for

the Drug Policy Alliance’s California Help Stop AIDS TV ad

campaign. He served as executive producer of Takeover: The Trials

of Eddie Hatcher (Golden Gate Award, San Francisco International

Film Festival; Jurors’ Selection, NC Film and Video Festival)

and is presently at work on The Berrigan Brothers: America is Hard

to Find. He is the proprietor of No Exit Productions, based in Kure

Beach, North Carolina.

Sisk is aboard the Liberty Star as a contracted writer and communications

consultant for the NOAA Undersea Research Program.