|

|

|

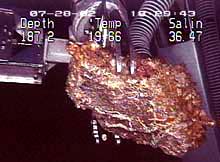

A large “live

rock” specimen is collected by the Johnson-Sea-Link

II at St. Augustine Reef. Click image for

larger view. |

| | Life on a Rock

July 29,

2002

Dr. Leslie Sautter

Geology Department,

College of Charleston

Project Oceanica

Watch

a video of a "live rock specimen". (QuickTime, 1

Mb) Watch

a video of a "live rock specimen". (QuickTime, 1

Mb)

One of our mission

objectives is to investigate the rock that makes up the foundation

of the underwater oases. On each dive we are reassured that where

there is rock, there is life! Where no rocks occur on the seafloor

(except buried beneath the surface), the seascape consists of a

blanket of sand that has few visible forms of biota. The rocks that

outcrop, however, are completely enveloped in invertebrate

organisms, to the point that not a square centimeter of the actual

rock surface is exposed.

|

|

|

Each rock is

photographed with a scale before we begin to pluck the

invertebrates from it. Many specimens were kept alive in

our shipboard aquarium. Click image for

larger view. |

| | To collect rock samples, we use the sub’s

powerful manipulator arm. Often the rock is too heavy to lift, or it

is firmly attached to the underlying rock pavement. Sometimes we are

able to recover a great specimen, which is then placed in the sub’s

collection basket. Once we are back on deck, the rock is hauled to

the wet lab for examination. I call this the “ooh-ahh phase” of the

research, when we examine and photograph the incredible biotic cover

of the live rock and begin documenting the specimen. It is at this

point that everyone—biologists, geologists, ship’s crew, and

others—all share in the excitement of the exploration. Watch the

video to see the initial on-deck processing of rock

samples.

Today we’ve had plenty of extra time to examine the

three rocks we recovered yesterday at the St. Augustine Scarp. On

each of these specimens, thick mats of brightly colored algae and

encrusting forms of both bryozoa and sponge wrap the rock surface in

a living cloak of vibrant color.

|

|

|

A turkey wing

mussel (Genus Arca) is found living within a bored hole,

firmly attached to the rocky substrate. Click image for

larger view. |

| | Soft coral, bivalves (e.g., clams and mussels),

barnacles, and polycheate tube worms all claim their own territory,

affixed to either the rock surface or in self-made, rock-lined bored

holes. A variety of small

crustaceans (e.g., crabs and amphipods), echinoderms (e.g., sea

urchins and brittle stars) make their homes among the pits and

holes, foraging through the dense overgrowth of their surrounding

environment. Worms that make specialized tubes in which to live are

numerous and can be found in a variety of forms.

All these invertebrates make their home on the

available hard seafloor, or “rocky substrate,” as they require an

immobile surface on which to live. The nearby Gulf Stream supplies

the region with strong currents, making the shifting, sandy seafloor

difficult to inhabit. This diverse group of opportunistic

invertebrates takes great advantage of any exposure of such

“hardground.” The rock-bound communities differ slightly from rock

to rock, perhaps due to local currents or other environmental

conditions. Local predators may also influence the community

composition.

|

|

|

Tiny tubes

built as housing by serpulid tube-worms were clustered

in a small forest-like grove on one of the rocks

collected. These tubes are approximately 0.5 cm in

length and were viewed through a dissecting microscope

on board the ship. Click image for

larger view. |

| | Once we return to shore, the rocks will be dried

until they no longer have an overpowering odor of decay (!). Then

they will be broken into smaller pieces and analyzed for their

mineralogical content (composition) and grain size. While on the

ship, however, we will continue to examine them as living rocks and

value them as the foundation of the deep underwater oases along the

edge of the southeast U.S. continental

shelf.

(top)

|

|

|