Research Goals:

Our primary goal for this mission is to use the multibeam sonar survey

to produce a high definition 3-D map of the bottom that will help us

define the exact extent of the reef system. Previous fathometer surveys

have been incomplete. The multibeam survey will provide details never

possible before. With continued funding our future goals are: to determine

how much live reef is left, to determine the extent of dead coral and

damage from trawling, and to continue long-term monitoring of fish populations

to see whether the fishing ban is helping with the recovery. Reef balls

have also been deployed in the crushed areas of the reefs to provide

habitat and structure for fish and coral to recover.

What are Oculina Reefs:

The deep-water Oculina coral reefs off central eastern Florida are unique

and occur nowhere else on earth. They are made entirely by a single

species of coral, the Ivory Tree Coral, Oculina varicosa. These form

mounds and pinnacles that are up to 100 feet tall and provide habitat

for an incredible diversity of fish and invertebrates. These reefs grow

below the Gulf Stream at depths of 200 to 300 feet deep, along the edge

of the continental shelf from Fort Pierce to Daytona Beach. In 1984,

NOAA and the National Marine Fisheries designated a 92 sq. mile portion

of the Oculina reefs as a marine reserve in order to protect the coral

from bottom trawling and anchoring. In 2002, the Oculina reserve was

expanded to 300 sq. miles, from Fort Pierce to Cape Canaveral; it is

called the Deep-water Oculina Habitat Area of Particular Concern (OHAPC).

The Importance of Oculina Coral as Habitat:

The Oculina coral provides habitat for an incredible diversity of fish

and associated invertebrates including 70 species of fish, 230 species

of mollusks, and 50 species of decapod crustaceans (crabs and shrimp).

Fish species include various grouper (gag, scamp, snowy, speckled hind,

warsaw), snapper, drum, porgies, sharks, amberjack, tuna, mackerel,

and giant ocean sunfish. Large populations of gag and scamp grouper

use these reefs as feeding and breeding grounds. Unfortunately by the

late 1980s the fish populations had been severely decimated from over

fishing, and in 1994 the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council (SAFMC)

placed a 10-year moratorium on bottom fishing to see if the grouper

populations could recover. Since some of these grouper species do not

breed until they are 10-15 years old, recovery will be a slow process.

Oculina is Delicate and Slow Growing:

Oculina coral is as fragile as china and is very slow growing. Deep-water

Oculina only grows about 1/2" per year. Bushes of Oculina grow

3-5 feet tall and may be centuries old. The reefs themselves may be

over 10,000 years old.

Fig. (A large coral head

of Oculina Varicosa, this particular coral head is over a century old.)

Human Impacts:

Unfortunately some areas of the Oculina reefs have been severely impacted

by human activities primarily from destructive fishing such as bottom

trawling destroying vast areas of the coral. As recently as last year

shrimp trawlers were caught poaching within the OHAPC and 8000 pounds

of shrimp were confiscated. Bottom fishing also can impact the coral

from heavy weights and fishing lines entangling the delicate coral and

over fishing has certainly impacted the fish populations.

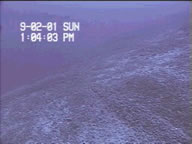

Fig. (This area on the

seafloor flourished with Oculina Varicosa, now it is a bed of broken

coral rubble. This section of reef was probably mowed down by a trawl

net, if you look closely you can see the ridges in the sediment where

the heavy “doors” of the trawl net have left their mark.)

Management Goals:

The recommended management goals and objectives are: to protect and

conserve the unique and fragile coral habitat; to ensure commercial

and recreational fish stocks; to create public awareness, education

and research; and to regulate activities that could harm habitat but

still allow non-detrimental commercial and recreational usage of these

resources. In 2004 the SAFMC will reassess the ban on bottom fishing.

Fig. (A reef ball has been

placed in an area of destroyed reef, to improve the growth of Oculina

corals and to provide habitat for native species.)

The Future:

Submersible studies in 2001 have documented that the populations of

scamp, gag, and snowy grouper appear to be greater than in 1994 prior

to the fishing ban. Although they are still nowhere near the population

densities present in the early 1980s, the good news is that they appear

to be beginning to recover. Our studies have also shown that the grouper

especially are attracted to the healthy reefs and very few are found

on the dead reefs. It is imperative that we continue to educate the

public, our government agencies, as well as commercial and recreational

fishermen that these reefs are unique, irreplaceable resource. We also

need better protection now. Although surveillance and enforcement will

never be 100%, we must prevent any future damage from irresponsible

poachers.

As you can see, our mission is vital to the survival of this one-of-a-kind

resource. Public awareness is the key!

SPECIAL FEATURE:

To keep you glued to your computer screen we're going to feature an

interview with a different scientist or crew member each day and get

the scoop on their job and how they got there…

Today we're going to interview scientist Stacey Harter (pictured

left), from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). The

NMFS is a branch of NOAA (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association).

Stacey is a Fisheries Biologist. She decided she wanted to go into marine

science when, as a teenager, she was watching a special on the Discovery

Channel about dolphins. It was then that she realized you can actually

have a job and get paid for doing marine science! During her undergraduate

studies Stacey did an internship in the labs at NMFS and ended up getting

hired there after she graduated. She has a Bachelor's degree in Biology

with an emphasis on marine science and recently got her Master's degree

in marine science.

Today we're going to interview scientist Stacey Harter (pictured

left), from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). The

NMFS is a branch of NOAA (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association).

Stacey is a Fisheries Biologist. She decided she wanted to go into marine

science when, as a teenager, she was watching a special on the Discovery

Channel about dolphins. It was then that she realized you can actually

have a job and get paid for doing marine science! During her undergraduate

studies Stacey did an internship in the labs at NMFS and ended up getting

hired there after she graduated. She has a Bachelor's degree in Biology

with an emphasis on marine science and recently got her Master's degree

in marine science.

Stacey's duties include a juvenile reef fish recruitment project, which

helps scientists predict the future population of specific fish species

such as certain grouper and snapper. For this project she catches fish

in a trawl net and measures them. For those that are already dead, she

takes them back to the lab to determine their ages. Another project

she is working on is on the W. Florida Shelf Marine Reserves. There,

she studies the effectiveness of the marine reserve with remotely operated

vehicles (ROV's), fish traps and video.

Stacey says the best part of her job is that she has a good mix of

field and lab work and isn't stuck in either one all the time. If she

had to pick something she likes the least it would be that being in

the lab for long periods of time can get rather boring!